Graffito

Pablo Rasgado’s Graffito is an ongoing architectural intervention that interrogates the boundaries between traditional art forms, public space, and the temporal nature of urban landscapes. The project, initiated in 2021, places fragments of oil paintings, a medium historically associated with durability and institutional preservation, into public and volatile urban settings. By embedding these pieces within diverse cityscapes—including Mexico City, Colombia, New York, and key locations in the West Bank—Rasgado reframes the purpose of the medium and its relationship to its surroundings.

Materials

Oil-paint (paint layer detached from canvas), urban walls, environmental conditions, pollution, and sociopolitical surroundings.

date

2021-2025

Exhibitions

⎖Centro de arte Limantour/Saenger gallery

⎖Piero Atchugarry Gallery at Zona Maco Sur

⎖Time based at Molaa, Long beach

Collaborators

⎖Eduardo Luque, Curator

⎖Christian Barragan, Curator

⎖Garbriela Urtiaga, Curator

⎖Majd Nazrallah, facilitator

⎖Yazid Anani, facilitator

Texts by

⎖Virginia Roy

⎖Dan Cameron

⎖Anna Mess

publications

⎖Ways of traveling, ed. A.M.Qattan Foundation

⎖Atea 10 años, ed. Atea

⎖أفق / Horizonte /Horizon ed. op.cit. and Sexto Piso

Texts

Published in:

⎖Ways of traveling, ed. by the A.M. Qattan Foundation

1.

When thoroughly analyzed, the chemistry behind the materials of a given artwork adds up to discourse, it can reflect on the time in which it was constructed, the place where it was created, the routes the material took, the technical development, and can even give hints about the socio-political climate of its era.

Oil painting, thanks to its chemical stability and slow drying process, results in a durable medium capable of withstanding significant changes over time. This technique has endured through centuries (1).

The careful layer-by-layer application, of selected sediment from the landscape (2), allows for a high degree of detail and depth in the depicted images, which quickly made it the preferred method for reproducing scenes, places, and characters—considered today as historical documents encapsulating the sites and customs of ancient times, predating the invention of photography.

The qualities of durability and stability have anchored this technique in the pictorial tradition of art history, infusing it with a precious longing. Like valuable objects, these works are safeguarded in museum institutions where dust, light exposure, and even temperature are meticulously controlled, preserving these quasi-archaeological artifacts within their vaults and allowing them to “escape the inexorability of time” (3). This condition recalls André Bazin’s reflections on the origins of photography and cinema, a media that, like painting and sculpture, originate from what he calls “the mummy complex” (4). This complex reflects a desire Bazin compares to ancient Egyptian religious practices, based on the polarization against death and the disintegration of the body, leading restorers to embalm the image in layers of varnish to attempt to extend the lifespan of the images.

2.

“Graffito” refers to a concept used in the field of archaeology to describe marks or inscriptions made by individuals since ancient times. Today, the evolution of this term into “graffiti” has been used to designate deliberate pictorial/material marks made on walls.

Graffiti, with only a 70-year history, was enhanced with the arrival of spray paint, allowing almost immediate application and drying, simplifying the pictorial process by acting as both brush and paint simultaneously. Spray paint was quickly adopted within social movements and protests, enabling unnoticed markings, subversive strategies, and subsequently, the formation of certain subcultures developing their own methodologies in the open sphere of the political and social.

3.

Graffito (2021-2023) consists of a series of site-specific architectural interventions carried out by artist Pablo Rasgado during recent visits to the Palestinian territory as part of the research and production residency “Ways of traveling” by the A.M. Qattan Foundation.

These interventions were placed by the artist on the walls of various buildings in Ramallah, Jerusalem, Hebron, Jenin, and Nablus, using a technique that allowed the detachment of the material layer (oil paint) from easel paintings. This material was then repositioned within the Palestinian landscape and, like grafts, incorporated inadvertently into the public sphere of these cities.

These paintings, all created using this durable material, when positioned within these contexts and outside the institution, will capture aspects of the environment, climate, as well as interactions with passersby. They are intended to act as markers, bearing witness to some of the constant changes occurring in this disputed territory.

Notes:

(1) Murals inside the tunnels in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, date back to 650 AD, and are the earliest known surviving oil paintings.

(2) Many pigments produced from prehistory to the present originate from natural sources, whether mineral and/or biological: soils, oxides, animal waste, parts of insects, mollusks, etc. The industrial revolution also expanded the spectrum of materials and processes, broadening the range of colors and possibilities of the medium.

(3) André Bazin, “What is Cinema? Vol. I,” trans. Hugh Gray (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967), p. 9.

(4) Ibid.

Landscape Scars

1. The Violence of the Wall

It was birthed from the womb of a concrete wall, a wall so hard it barely shows the words I etch upon it. It is a text born of iron and concrete.

Nasser Abu Srour

The wall, the barrier, cuts through and signifies the history and landscape of Palestine. It is present in the historical exoduses of communities, in the refugee camps, and also in the continuous checkpoints of the Israeli army. The land is scarred and fragmented by divisions, by the houses ruined by settlers and soldiers, by precarious constructions and abandoned villages, creating invisible walls and others that are more lethal. The presence of these physical and architectural boundaries is constant in the area. It speaks to us of a past that has lingered and endured, but also of the necessary conditions for inhabiting the present and of the complex possibility of shaping a future. The horizon of Palestine is defined by borders and demarcations, and above all, by the deep-rooted presence of its people and their defense of the territory.

In his book The Tale of a Wall, Palestinian writer and prisoner Nasser Abu Srour describes the wall’s omnipresence in his life: from his childhood in a refugee camp to his current imprisonment in an Israeli jail, where he maintained a dialogue with it for over 30 years: “This is the story of a wall that somehow chose me as the witness to what it says and what it does […] The wall has conferred upon me all my defining traits and all the names I have been known by—in the camp, on the outskirts of the city, in prison, and in the heart of a woman”.[1] For Abu Srour, it is the wall that tells the story — of what has happened and been lived. Inscribed upon it are the history and the resistance of generations of uprooted Palestinians and separated families. A wall, seemingly inert, becomes the testimony of a struggle.

On the other hand, any border emphasizes the idea of inside and outside, the segregation of land and communities, of being fenced in, watched, and controlled. The Palestinian landscape embodies narratives of war and occupation, and its barriers reflect the violence of the territories. Architecture is not harmless, nor are materials innocuous — they are a means of response, as an expression of the place’s resistance. Walls become voices and cries; fences are amplified, and historical and present wounds resound.

2. Memory of the Territory

Our map is disrupted by settlements, and our cities have become suffocating spaces that are hard to leave. Even just to look at the sea.[2]

Lina Meruane

The dialogue that Mexican artist Pablo Rasgado establishes with walls and surfaces sends us back to the violences inscribed in the territory, through the layers of memory. His work is characterized by a physical and material investigation of space and its relationship to architecture — both within the institutional white cube of the museum and in the tensions of public space. His interest in construction materials and building processes, in the fragments and traces they produce, as well as in the very structure of architecture itself, allows him to unravel strata of memory and material imprints that shape the elements within space.

In earlier works, Rasgado engaged, for instance, with the inner workings of the museum and proposed reusing walls with the intention of exploring the concepts of accumulation, installation and residue. For his project Unfolded Architecture (2012), he asked the Carrillo Gil Museum, in Mexico City, to retain the false walls used in exhibitions over the course of a year, for him to use them as material for his work. This reorganization of the recovered panels and leftover museographic materials was presented in a new two-dimensional arrangement, stripping them of their original volume and giving the elements a different life and materiality. As the artist himself has noted, “These works propose rethinking the solidity and immovability of walls, analyzing residue, revealing ghosts, and reflecting on what precedes us in a specific site […] In interaction with institutional and contextual issues, the material is proposed as a point of departure capable of making hidden layers of the environment visible and of directly shaping the resulting image.” [3]

Rasgado’s artistic practice also examines the temporalities and textures inherent in pictorial mediums such as oil painting, fresco, or graffito. For his Pinturas murales series, he uses the strappo technique — a method primarily employed during the Renaissance to detach wall paintings by separating the chromatic layer from the surface finish. It is the method famously used to transfer Francisco Goya’s paintings from the Quinta del Sordo. In his Pinturas murales,[4] Rasgado lifts the very “skin” of walls from the streets to constitute autonomous paintings. The series began in 2007 in Havana, Nebraska, and Illinois, and continues to this day, having delved into the public sphere of cities such as Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Paris, New York, Philadelphia, Charlotte, Bogotá, Lagos, Los Angeles, Tel Aviv, Ramallah, and Paris.

Rather than a mere relocation, this action is an exercise in decontextualization that functions as a strategy for resignification. Such “connotated recomposition” thus emphasizes the importance of the framing of the presentation. The skin of the surface speaks, reveals, and proposes, and the remnants become protagonists in a new configuration —materials found from and upon found spaces. Rasgado’s practice insists on the expressiveness of pictorial media and the semantic potential of space, as well as materiality as an exercise in identity. His work delves into the syntax of the surface: the language of fissures, cracks, and fractures.

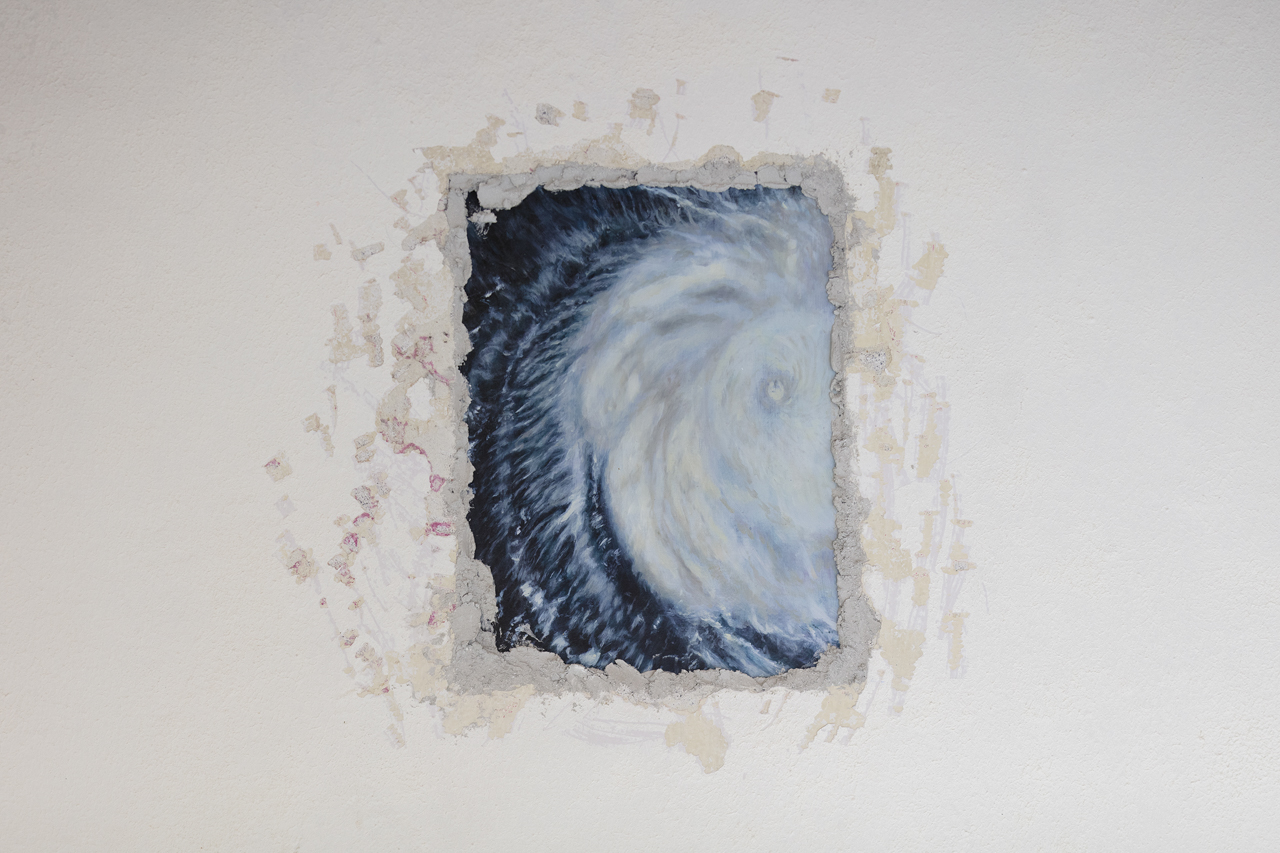

In 2017, Rasgado began his Graffito project, a series of interventions carried out in the San Bernabé neighborhood of Mexico City, Brooklyn, New York, and later in the cities of Ramallah, Jerusalem, Hebron, and Jenin in the West Bank (2019). The work consisted of figurative oil paintings, previously created by the artist in his studio, which he later relocated onto walls in urban spaces —the reverse exercise of Pinturas murales. Thus, The paintings were removed from their original support using the strappo technique (previously employed by the artist), and then reinstalled onto walls in various cities. Through this layering of surfaces, Rasgado explores the recirculation of representations in new contexts. He places another substance, another body atop the wall, creating a new material overlay that introduces a different meaning. This covering generates a displacement and movement of forms that points towards a new dimension of the urban, but also of the human.

The title of the project, Graffito, clearly alludes to the graffiti technique as an ephemeral intervention in public space, but also to the origin of the word itself, referencing marks and inscriptions in the field of archaeology, made since antiquity. In this way, the relocation of original paintings into public streets highlights the contrast between the distinct temporalities intrinsic to each technique. The traditional durability of oil painting dissolves when inserted into an open environment, immersing itself in the perishable nature of graffiti. The endurance of the oil paint, exposed to the elements and the flux of the city, creates a new stratum of memory, as well as uncertainty about its future. Yet beyond its physical and inevitably transient presence, the paintings also become extinguishing timekeepers — marks that compel us to rethink what survives and endures and above all, what ultimately transcends human time.

The images in this series do not depict people but rather landscapes and places that open new horizons: mountains and skies; trees and forests; lakes or ponds, and even the sea. The forms and elements of nature become embedded in the ruin and porosity of the walls. In some cases, this happens over a white background, and in others, with a transparent substrate, but the image always fades into the surface and merges into the wall. In this way, the repositioned images create what could be called a “chronolandscape”: that is, a representation of the conjunction of times and memories onto the materiality of the wall.

The different times contrast and overlap; they stretch and shrink, configuring a landscape in flux. In the artist’s words: who sees that landscape and reads the image? Who produces the landscape in its immensity?[5]

3. Fusion of Horizons: the Concrete and the Infinite

[…] soldiers did not often use the streets, roads, alleys, or courtyards that constitute the syntax of the city, as well as the external doors, internal stairwells, and windows that constitute the order of buildings, but rather moved horizontally through party walls, and vertically through holes blasted in ceilings and floors. […] Moving through domestic interiors this maneuver turns inside to outside and private domains into thoroughfares.[6]

Eyal Weizman

The precarious nature of construction in Palestine, combined with the constant attacks by the Israeli army, makes the concept of domestic and private space both diffuse and complex. For years, the military has used buildings —architecture itself— as a means of attacking the population. In the words of Eyal Weizman, the urban space becomes a weaponized medium. “The tactics of walking-through-walls involved a conception

of the city as not just the site, but as the very medium of warfare – a flexible, almost liquid matter, contingent and in perpetual motion”.[7] In this way, the offensive ceases to be a classic linear confrontation and instead transforms into a decentralized assault—less visible and more effective—enabled by the military tactic of the swarm, in which Israeli soldiers drill through walls and infiltrate homes. There is no safe space in Palestine—not even one’s own home.

In the face of the instability and fragility of walls and structures, of collapses and ruins, Rasgado’s artistic proposal is to highlight and imbue them with connotations as places of materiality and resistance. In a metaphorical and poetic way, the Graffito project presents another dimension of rupture with the wall, of the dissolution between outside and inside. The canvases superimposed in public spaces emerge as a new landscape opened from the wall, one that creates perspective and depth.

Mostly figurative depictions of recognizable natural elements, the paintings are inserted into the formal neutrality of the wall, contrasting with its material abstraction. A tension between figuration and abstraction becomes evident within the two-dimensional plane created by the Graffito interventions. This tense relationship, in turn, highlights the opposition between imagination and reality: between the fantasized, projected, and simulated painted landscape, and the wall as a real, tangible backdrop and support, in other words, between the existent and the allegorical within the same space.

On the other hand, the analogy with the figure of the window is clear—its etymology deriving from the word wind. Through the window, we access another reality: an ephemeral opening that overlays the structure of the wall like a cut-out of reality. In this way, the rigidity of the Palestinian walls begins to crack, and space emerges and projects itself. The wall expands and becomes a viewpoint from which to contemplate the landscape. Through this metaphorical dilation, the widened wall narrates another horizon that expands outward as infinite potential. Thus, a juxtaposition is created between the fixed structure of the wall and the infinite projection opened up by the image.

For Rasgado, the work also goes beyond the notion of the window and of painting as a genre, functioning instead as a resonance chamber and a surface that captures the subtleties of its environment—both atmospheric and social. It becomes a thermometer that documents the pulse of a territory in conflict.[8] It reveals a social landscape, a disputed land. An amalgam of representational scenarios inscribed on the body of the wall: a fusion of horizons, views, and expectations. As mentioned at the beginning, drawing on the words of Abu Srour, the wall is testimony, and in its ruin and remains, it reveals its position. It opens the possibility to think and imagine a horizon of potential: of trees, of sea.

Palestinian writer Fadwa Tuqan reflects on this landscape that both narrates and resists:

“The waves carried us

To a shoreless sea,

Limitless

And without resistance

So the waves would tell

The eternal story of life.”[9]

[1] Nasser Abu Srour, The Tale of a Wall, Other Press, New York, 2024, p. 3.??

[2] Lina Meruane, Palestina en pedazos (Palestine in Pieces), Random House Mondadori, Mexico, 2024, p. 85

[3] Conversation with Pablo Rasgado on April 12, 2025

[4] In this same line of work, the artist’s Timescapes series, shown at the Steve Turner Gallery in Los Angeles (2021), stands out.

[5] Conversation with Pablo Rasgado, April 12, 2025

[6] Eyal Weizman, Walking Through Walls, extradisciplinaire, 01 2007: https://transversal.at/transversal/0507/weizman/en

[7] Op. cit.

[8] Conversation with Pablo Rasgado, April 12, 2025

[9] Fadwa Tuqan, “Las olas”, in Ante la puerta cerrada, (1967) Cuaderno 35 de Poesía Visual “Entre los poetas míos”, Bilbioteca Virtual, June 2013: cuaderno-de-poesia-critica-n-035-fadwa-tuqan.pdf

TIME STOOD STILL

The structural weaknesses that are endemic to our shared, perception-based systems of representation are nowhere more glaring than when it comes to territory that is violently contested, as it’s subject to changing hands, or shifting from the state of possession to dispossession, with little to no warning. Also, there are always multiple competing narratives implicit in the notion of contested territory, which means not only that there is no eyewitness perspective capable of conveying the entire story, but also that such a capacity is diminished ever further when one of the parties is no longer present. What can our senses really tell us about such a situation, other than to confirm that a building once found at a specific location is no longer there, or that there is no family currently living at an address? Our natural instinct for sentimentality would have us believe that a photograph, a personal effect, or the sound of someone’s voice can serve as a proxy for whomever or whatever is no longer present, but nobody who’s experienced the grief of intense loss is fooled for a minute. In order to represent something which has been swept away through brute force, while also moving it beyond the pull of unchecked subjectivity, it is necessary to first ask oneself what set of criteria will satisfy our need for objective evidence of that which once was, but is no more. How far can a forensic investigation take us inside a reality that can only be conveyed

Pablo Rasgado’s artistic practice has long been engaged with testing the outer limits of representation, especially when it comes to areas where meanings are more likely to be distorted or misrepresented. To make clear his disinterest in employing our senses as an instrument for reinforcing a sense of stability, his work often takes the form of objects or installations that appear to be in the process of canceling themselves out, or at least undermining whatever appearance of stability they might have had before he began to engage with them. In one case, Rasgado’s site-specific contribution to a 2014 group exhibition in New Orleans organized by this writer consisted of a pair of faux architectural columns designed both to look visibly credible, while giving the impression of an architectural feature that had been stripped of its solidity between ceiling and floor, and twisted into a knot before returning to its more prosaic form. The illusion that the “columns” were there for support was curiously bolstered by the impossible twist in the center, even though, if real, they would have caused the entire ceiling to collapse.

For the 2016 Biennial de Cuenca, whose theme was Impermanencia, Rasgado took on the project of representing the human body by using the chemicals and minerals present in human blood, tissue and bones to produce a series of presentations in which the process of making the work began by obtaining the original materials — blood, saliva, urine, sweat, hair, kidney stones, et. al. — from specific individuals. Each specimen was extracted and synthesized into crystalline form through established laboratory protocols, so that no matter its state when it left the subject’s body, it wound up on a plinth as geological residue. Rasgado refers to this process as “micro-portraiture,” in which the specifics of each individual would no longer be traceable back to their biological reality. His interest, however, is in contextualizing the human experienc within a temporal framework that is closer to archaeology, when its chemical fingerprint would be measurably useful. If as the proverbial dust from which we came, and to which we shall return, we invariably lose our specificity along the way, our mineral traces still remain tied to our exact presence in a specific time and place.

The issue at play in Rasgado’s proposition isn’t so much that we as human beings are incapable of grasping time using an archaeological or geological framework, in which centuries and millennia might pass in the same manner that we experience weeks and months. Rather, if the goal to be achieved is a methodology of representation, then bearing witness to the mineral content of someone’s blood should be just as intimate as contemplating an urn filled with a loved one’s ashes. Indeed, there is something about a crystalized substance that we immediately associate with a form of permanence, and if we wish for the deceased loved one to remain in our thoughts into perpetuity, it seems that the same quantity of iron, calcium, magnesium or sodium that they held in their body could be at least as potent a memorial as an indiscriminately charred mass intended to be tossed into the sea.

The activity that Pablo Rasgado was invited to Palestine to undertake between 2020 and 2023 was that of the investigator. Making his way by vehicle and foot through the roads, streets and checkpoints comprising Palestinian territory, he made multiple extended visits, partly as a way of experiencing communities directly, buildings, sites, homes and ruins, accompanied by colleagues or on his own, speaking with people he met, and sometimes accompanied principally by his own observations. The subject of Rasgado’s investigation was Palestinian life and culture as embodied in its architecture, which in the years prior to the events of October 7, 2023 had already experienced radical transformation in communities on the West Bank and in Gaza Strip, and he got to know private homes as well as places that have been points of reference in the public lives and collective identities of communities striving to maintain a stable existence. Rasgado’s return visits over four years of research intensified his feeling that what had at first seemed fixed and static later could be perceived as part of a far more dynamic flow.

Rasgado’s resulting proposal, Horizonte, was developed for a group exhibition based on the results of his research (and that of seven other artists), which was originally scheduled to take place in 2024 and has now been postponed indefinitely. Applying the principle of crystallization developed for his Cuenca project, Rasgado again approached the problem of representation from the perspective of geological time, with the built environment of contemporary Palestinian territory as his subject. Seen in this framework, at some point in the distant future, everything that is present today will remain in the form of a geological layer made up of crushed materials used to build the buildings we currently occupy. It is a form of micro-portraiture writ large, in which instead of getting a specific individual, we’re getting the crystallization of a place.

What does it imply to speculate about a possible future version of the world we currently inhabit, say a hundred thousand years in the future? The question isn’t meant to conjure at the fanciful image of archaeological digs undertaken by intergalactic aliens, but as a way to return to Rasgado’s prior example of representation as it relates to the human body. If in fact a person can be credibly reconfigured as a tidy bed of petrified calcium oxalate, then the same principle can be applied to the walls, roof and floors where we carry out our lives, and which are made using building materials produced from compounds, mostly non-recyclable, that have a precise chemical signature that might provide solid data about who lived here and under what circumstances they left.

For Rasgado, taking the very, very long view of history has the secondary advantage of underscoring how rigidly conventional temporal frameworks limit our ability to develop any critical distance with what is taking place in the present moment. Our tendency is to measure time in days and hours, but when circumstances demand, we are also capable of identifying and analyzing patterns and cycles that occur across years and decades. Not everything that takes place needs to be, or can be, fully explained within the immediate context of the event in question. We really do see things differently with the passage of time, which can be a useful tool in facing the immediate future and predicting specific outcomes, and few of us are immune to the occasional reflection on how one’s life might be today had certain episodes in the distant past turned out differently. It is this capacity, key to being human, for speculating about time through a framework of events that haven’t happened yet, along with events that never took place, that Rasgado is calling on for us to experience his understanding of the sense of place he decided to articulate as the result of his residency.

Of course, the crystallized essence of a mineral is not equivalent to a home, or to a person, nor is the artist expecting us to believe that it is. What Rasgado is inviting his viewer to do is consider a specialized discipline such as geology or archaeology as conveying a readymade perceptual methodology that contrasts with our own tendency to come to hasty conclusions during the heat of the moment. Invited to converse, break bread, and share observations with people who in some cases were living in locations whose future viability is far from certain, Rasgado likely came away from his series of exploratory visits to Palestinian territory with multiple written or verbalized approaches in mind that might suffice to convey his impressions, but still at something of a loss about how to make the experience tangible. How does one convey the many changes of a neighborhood market, a hillside, or a family, over a four-year period when the anxious, nagging fear that what you’re experiencing is transitory hangs over it all?

A key part of Rasgado’s process, and what makes it especially applicable in this circumstance, has to do with the underlying principle of specificity. The samples of saliva and kidney stones used in his micro-portraits were taken from specific individuals, not through anonymous sourcing. How does this impact the way we think about portraiture? While the crystalized stones might not in any way resemble the person from whom they were obtained, we can rest assured that they really are that person, far more than a portrait could ever be, no matter how accurate the likeness. The same applies to the samples that he collected from particular sites, and that become part of the transformation of the individual portraits into the collective portrait of an entire society. By providing us with a zone of reflection where awareness, imagination and hard data can come together, Rasgado provides us as well with his version of a primary truth: this is who we are.

DAN CAMERON is a curator, art writer, archivist and visual artist based in New York City.

Published in:

⎖Atea 10 Años,

Cuando una obra de arte determinada es analizada a profundidad, la información que provee la química de los materiales, se suma al discurso y puede llegar a reflejar la época en que fue construida, el lugar donde se creó, las rutas que tomó el material, el desarrollo técnico e incluso dar pistas sobre el clima sociopolítico de su era.

La estabilidad de la pintura al óleo, gracias a su composición química y lento proceso de secado, resulta en un medio durable capaz de evadir grandes cambios a través del tiempo. Esta es una técnica que ha perdurado a través de los siglos, como lo atestiguan pinturas al óleo que datan de 650 d.C. (1)

Se trata de un medio que, a través de la cuidadosa aplicación, capa por capa de sedimentos selectos del paisaje, (2), permite un alto grado de detalle y profundidad en las imágenes plasmadas, lo que llevó a esta técnica a convertirse rápidamente en la predilecta para reproducir escenas, lugares, y personajes, mismos que actualmente son considerados cuál documentos históricos y que encapsulan sitios y costumbres de épocas antiguas, previas a la invención de la fotografía.

Esta cualidad de durabilidad y estabilidad han arraigado a la técnica dentro de una tradición pictórica en la historia del arte y le han conferido un anhelo preciosista al medio que, cual objeto valioso, ha de ser resguardado en instituciones museísticas donde el polvo, la exposición lumínica e incluso la temperatura son minuciosamente controlados, preservando estos cuasi-artefactos arqueológicos dentro de sus bóvedas,y permitiéndoles “escapar a la inexorabilidad del tiempo” (3), esta condición recuerda las reflexiones de André Bazin acerca de los orígenes de la fotografía y del cine, medios que, al igual que la pintura y la escultura, se originan en lo que llama “el complejo de la momia”(4) y consiste en un deseo, que Bazin compara con prácticas religiosas del egipto antiguo, basadas en la polarización en contra de la muerte y la desintegración del cuerpo, que para las artes lleva a restauradores a embalsamar la imagen en capas de barnices intentando asi extender su tiempo de vida.

“Graffito” refiere a un concepto que ha sido utilizado en el campo de la arqueología para describir a marcas o inscripciones realizadas por individuos, desde la antigüedad. En la actualidad, la evolución de este término hacia el “graffiti” ha sido utilizado para designar marcas pictóricas/materiales hechas de forma deliberada sobre muros.

Esta técnica, con apenas una historia de 70 años, fue potenciada tras la llegada de la pintura en aerosol que permite una aplicación y secado casi inmediato, simplificando el proceso pictórico al actuar cual brocha y pintura simultáneamente, y al posibilitar cubrir áreas arquitectónicas de gran escala a través de la manipulación de la boquilla.

La pintura en aerosol fue rápidamente adaptada al interior de movimientos sociales y protestas, permitiéndo pintas inadvertidas, estrategias subversivas y, posteriormente, la conformación de subculturas que desarrollarían sus propias metodologías tomando como herramienta éste medio pictórico que surge para el espacio público, en la esfera abierta de lo político y lo social.

Graffito (2021- ) consiste en una serie de intervenciones arquitectónicas para sitios específico realizadas por el artista Pablo Rasgado sobre los muros de diversas edificaciones, en sitios específicos como son: San Bernabé CDMX, Brooklyn NY, Ramallah Palestina, Jenin Palestina, así como en un la calle de Topacio, al centro de la Merced en Ciudad de México y donde actualmente se encuentra ATEA,

Estas intervenciones fueron realizadas mediante una técnica que le ha permitido al artista, el desprendimiento de la capa material (pintada al óleo) proveniente de pinturas de caballete, para su posterior reposicionamiento dentro del paisaje, y que -a manera de injerto-, fueron incorporadas de manera inadvertida, dentro de la vía y esfera pública de estas ciudades.

Las pinturas, todas ellas realizadas por medio de este material duradero, al ser posicionadas dentro de estos contextos y fuera de la institución, grabaran sobre su superficie facetas del entorno, del clima, así como su interacción con los transeúntes y están pensadas para actuar como una suerte de marcadores, que atestiguan algunos de los cambios que de manera constante suceden dentro de estos contextos.

Notas

- Los murales dentro de los túneles en Bamiyan, Afghanistan, datan del 650 d.C.

- Una gran cantidad de los pigmentos que se producen desde la prehistoria hasta la actualidad, provienen de fuentes naturales, ya sea de origen mineral y/o biológico: tierras, óxidos, desechos animales, partes de insectos, moluscos, etc; y a partir de la revolución industrial el espectro de materiales y procesos amplió también la gama de colores y posibilidades del medio.

- Andre Bazin, What is Cinema? Vul. I, trans. Hugh Gray (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967), p. 9.

- Ibid.

pablo rasgado, Graffito (Ramallah), 2023. Oil paint on a wall, Site-specific.

Graffito (Ramallah)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Destroyed

no. 01

Title

Graffito (Ramallah)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (Mexico city)

Site:

Building about to be demolished, Cuauhtemoc, cdmx

Status:

Destroyed

no. 02

Title

Graffito (Mexico city)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (Ramallah)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Destroyed

no. 03

Title:

Graffito (Ramallah)

DATE:

2023

media

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (Ramallah)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Destroyed

no. 04

Title

Graffito (Ramallah)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (Mexico city)

Site:

Building about to be demolished, Cuauhtemoc, Mexico city

Status:

Destroyed

no. 05

Title

Graffito (Mexico city)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable Measures

Graffito (Ramallah)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Unknown

no. 06

Title

Graffito (Ramallah)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala No. 1 (Grisalla)

Site:

Oil painting embedded within the layers of a wall

Status:

on site

no. 07

Title

Cala No. 1 (Grisalla)

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on Masonite embedded in wall, site-specific

dimensions

Polyptych, variable dimensions

Graffito (Ramallah)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Destroyed

no. 08

Title

Graffito (Ramallah)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala No. 2 (Counter shot)

Site:

Oil painting embedded within the layers of a wall

Status:

on site

no. 09

Title

Cala No. 2 (Counterfield)

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on Masonite embedded in wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala No. 3 (Derrumbe)

Site:

Oil painting embedded within the layers of a wall

Status:

On site

no. 10

Title

Cala No. 3 (Derrumbe)

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on Masonite embedded in wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala No. 5 (Mise en abyme)

Site:

Oil painting embedded within the layers of a wall

Status:

On site

no. 11

Title

Cala No. 5 (Mise en Abyme)

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on Masonite embedded in wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala No. 7

Site:

Oil painting embedded within the layers of a wall

Status:

On site

no. 12

Title

Cala No. 7

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on Masonite embedded in wall

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala no. 8 (IMPASTo)

Site:

Oil painting embedded within the layers of a wall.

Status:

On site

no. 13

Title

Cala No. 8 (Impasto)

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on Masonite embedded in wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Cala no. 10 (second skin)

Site:

on Found painting

Status:

on view

no. 14

Title

Cala No. 10 (Second Skin)

DATE:

2025

medium

Oil on masonite embedded on found painting

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (La Merced, Mexico City)

Site:

Status:

on site

no. 15

Title

Graffito (La Merced, Mexico City)

DATE:

2024

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific intervention

dimensions

Variable measures

Water Lilies

Site:

Palestine, left on site for a year, Detached and placed on canvas

Status:

Retrieved

no. 16

Title

Water Lilies

DATE:

2022-2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, detached and placed on canvas

dimensions

120 x 120 cm

Remains Tomorrow

Site:

Palestine, left on site for a Month, Detached and placed on canvas

Status:

Retrieved

no. 17

Title

Remains Tomorrow

DATE:

2022-2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, detached and placed on canvas

dimensions

90 x 120 cm

Graffito (Ramallah)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Destroyed

no. 18

Title

Graffito (Ramallah)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on wall, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (Jerusalem)

Site:

Jerusalem

Status:

Unknown

no. 19

Title

Graffito (Jerusalem)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil paint on metallic door, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

Graffito (Hebron)

Site:

Ramallah, Palestine

Status:

Destroyed

no. 20

Title

Graffito (Hebron)

DATE:

2023

medium

Oil pain on metallic door at the city´s market, site-specific

dimensions

Variable measures

projects