Afterlife

Afterlife is a series by Pablo Rasgado that explores the spectral persistence of lost artworks—paintings that have disappeared, been destroyed, or faded, yet survive through photographic reproductions in catalogues and archives. Drawing on Aby Warburg’s concept of Nachleben (afterlife), Rasgado reanimates these absent works by recreating them in oil, not from the original paintings but from their photographic surrogates. Rendered in grayscale, these replicas inhabit a space between translation and forgery, collapsing the boundaries between image and memory, original and copy, presence and loss.

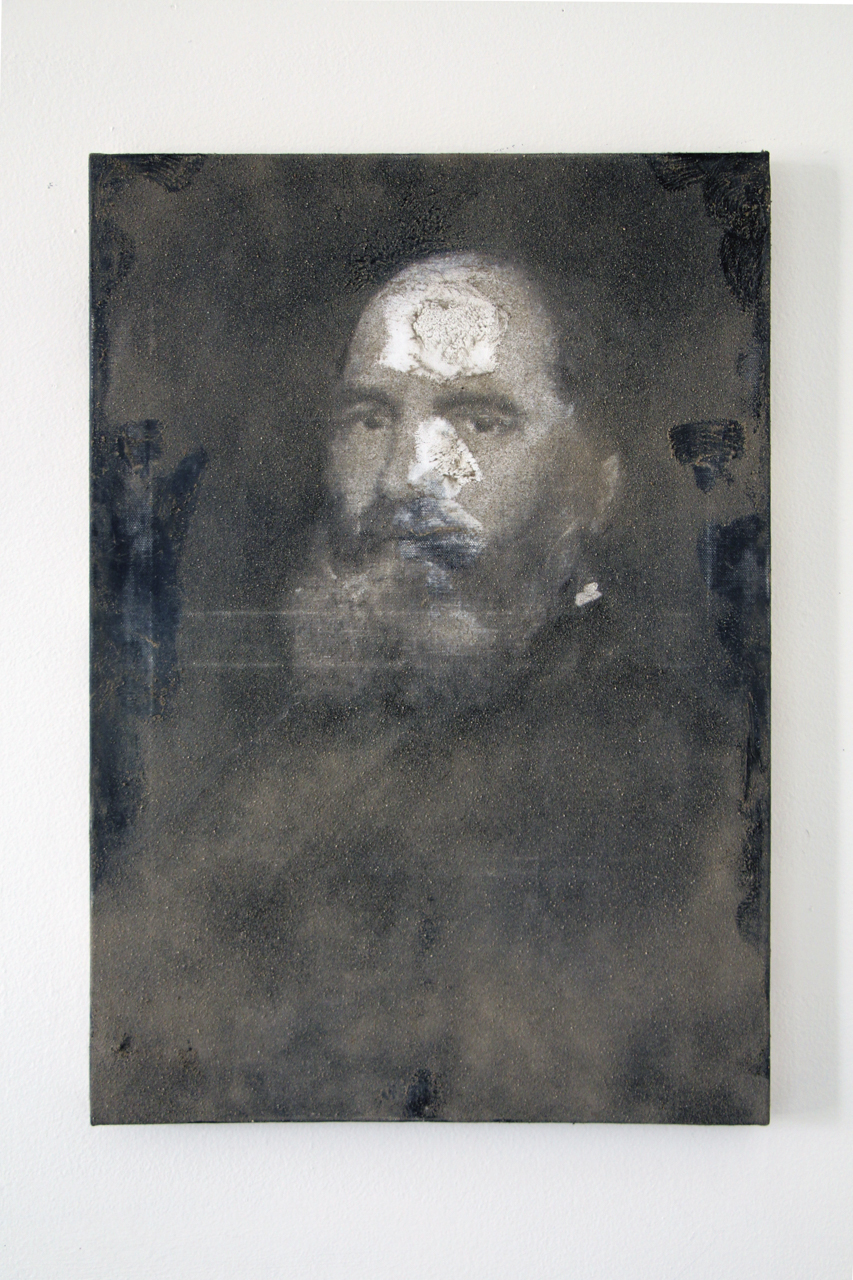

Once completed, the paintings were installed and left for months in a decaying Baroque residence in Paris, where they passively absorbed the dust, debris, and movement of time. Later, Rasgado intervened them again—excavating through the grime to reveal traces of the underlying image, merging acts of painting, erasure, and restoration. Afterlife becomes both an archaeological and painterly gesture, where dust is not just decay but a medium of transformation—marking the artworks with new temporal and material layers, and questioning what it means for an image to endure beyond its physical disappearance.

Materials

Oil on canvas based on archival photographic reproductions, environmental dust, debris, and adhesive-bound particulate matter.

date

2014

Exhibitions

⎖ ArtBasel Switzerland

⎖Arratia beer Gallery, Berlin

Collaborators

⎖Cité Internationale des Arts, Facilitator

⎖IFAl, Facilitator

⎖Carrillo gil museum, Facilitator

⎖École des Beaux-Arts, Facilitator

⎖Bibliothèque Kandinsky at the Centre Pompidou, Facilitator

Texts

⎖Eva Wilson

publications

⎖"Afterlife" ed. by beau désordre press

Texts

Published in:

⎖Afterlife, exhibition catalogue

At the beginning of the 20th century, Aby Warburg constructed his famous Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek in Hamburg around a classification system that was haunted by different categories of afterlife. As Georges Didi-Huberman explains, Warburg understood “Nachleben” as a structural term, not as a chronological one. He was interested in how antiquity lived on, resonated in different ages, sometimes by way of misinterpretation or complete reversal of original connotations, sometimes in iconoclastic clashes reacting to a sense of uncanny energy emanating from a work of art. Warburg “anachronised” history, folding time onto and into itself. Can a work of art die, does it have to die in order to have an afterlife, and what does this afterlife look like, encompass, entangle?

For his new series, Pablo Rasgado has delved into the depths of catalogues raisonnés, into the Bibliothèque Kandinsky at the Centre Pompidou and other fathomless archives in an attempt to recover lost images. You may argue that every research is an endeavour to retrieve or discover something that is lost or at least unknown. In Rasgado’s case however the objects he pursued had to remain lost in order to be singled out and reclaimed.

Rasgado was searching for the blind spots of art history: The images that his serendipitous investigation has disclosed were those that have gone missing, that have been misplaced, destroyed, forgotten, or stolen at some point in their biography, whose provenance expired into the status “present whereabouts unknown.”

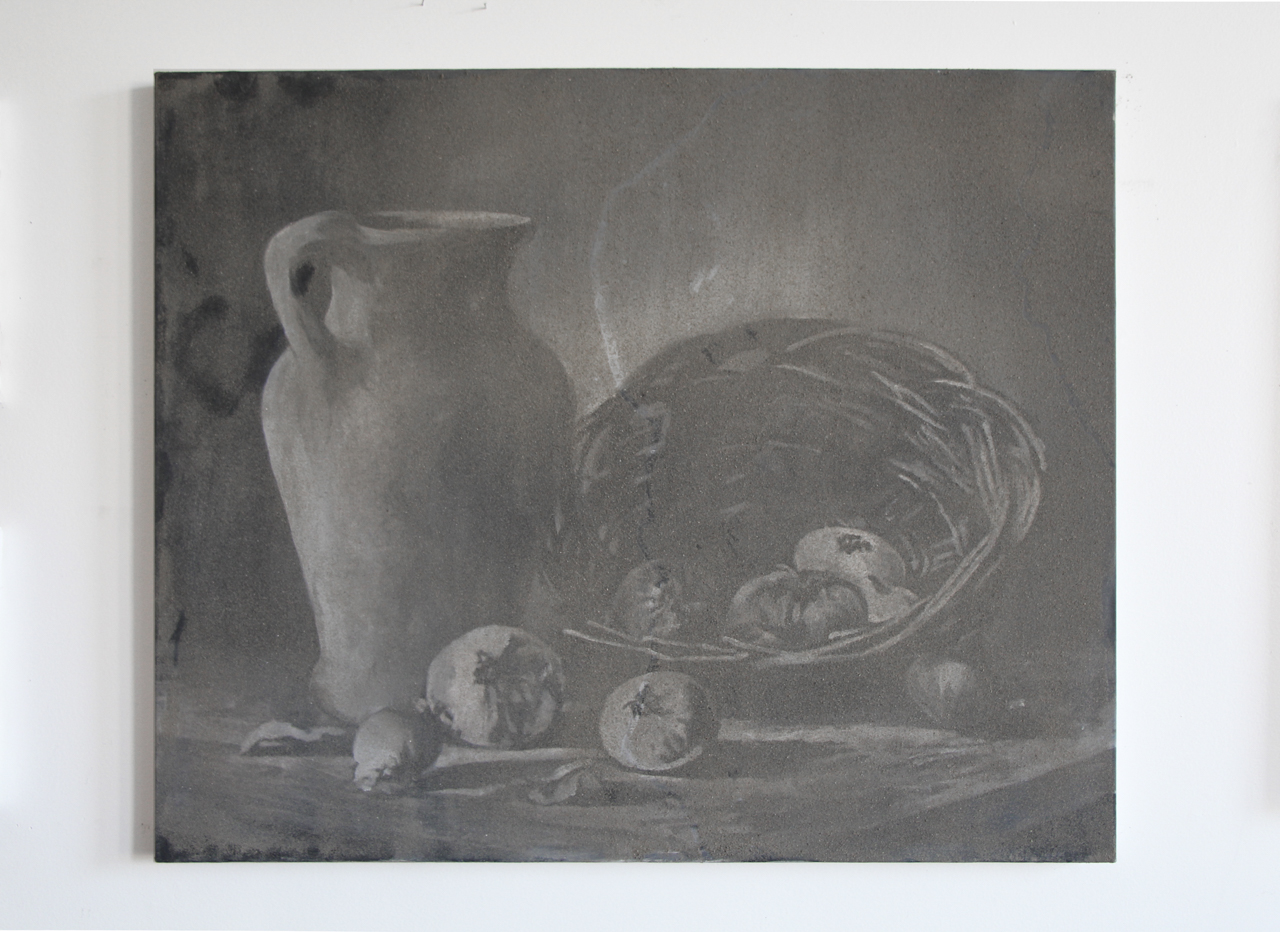

This uncertain status was the uncanny energy that set Rasgado’s method into motion: as revenants, as undead images stemming from disparate moments of the past he anachronistically reanimated these absent paintings by producing replicas, forgeries in a way, or mimicries based on their photographic reproductions in books and catalogues. Together with an assistant, Rasgado set himself the task of repainting these works in their actual size and as close to the original as possible. In the absence of the paintings as models for the replica however the new images mimic not their originals but rather their surrogates, the photographs, in regard to the amount of detail and most importantly their colour palette: most of the re-painted works adopt the greyscale of the photographs taken at some point over the last century and transform the reproduction into an oil grisaille.

Accordingly the paintings chosen by Rasgado necessitate two predicaments: that they are nowhere to be found, and that at some point before their loss they were photographically recorded. Rasgado collides the media and genres of painting and photography and with them their many complex evocations of the absent, of their status as emanation or representation of something that they are not. He also collides two distinct chronologies: The paintings date back to the 1440s up to the 1960s, but their photographic records follow a different and independent timeline, as well as a very distinct phenomenological status.

A painting renders its object visible and tangible in a very different way than a photograph does. Rasgaldo calls to attention images that only survive grace to their translation into another, more mobile, more ephemeral medium (the Latin translatio indicates the removal of relics from one place to another), thereby adopting a spectral presence flowing through unlimited printed reiterations. Their reincarnation once more as paintings obfuscates identities on several levels: that of the painting itself (it is alike but it is not alike), of the author of the image (the painter, the photographer, the forger), and of the status of the new work: as original, as reproduction, and as palimpsest.

Volcanic eruptions and Aeolian flows (the movement of matter caused by wind) stir the dust of aeons. Dust consists in part of human debris, animal hair, pollution, or pollen. Other elements of dust are burnt particles of meteoroids, space dust, interplanetary matter. Rasgado, after recreating the lost paintings by Bellini, Velázquez, Léger, Balthus, etc., placed the canvases in a palatial building in the centre of Paris, in the Rue Vieille-du-Temple near the Archives Nationals, its heavy wooden door adorned with the head of a Medusa. The building is partly abandoned and has been left in a state of slow decay for many years. Occasional building works and solitary figures moving through the Baroque parlours and crossing the intricate marquetry of the halls disrupt the dust of ages resting stoically on golden stucco and blunt mirrors and set it into gentle motion.

Rasgaldo’s paintings, placed nonchalantly on the floor, along the Palais’ walls, and in remote corners, acted as attractors to this dust, binding it to their surfaces by virtue of an adhesive, working their magnetic forces over the course of several weeks. A thick layer of grime, grit, of ashes, smut, of time, life, and death, of meteor dust and cosmic components, of the abject, of excretion, of entropy and decay now clings to the cheeks of Philip IV, to Bellini’s Madonna, to Goya’s Stone Guest. The paintings have camouflaged themselves under a veil of dirty matter, adopting a new skin and a new amalgamation of archaeological continuity compressed into debris. In their exposed placement on the palace’s floor, the paintings attracted over patrons, too: A snail calmly traversed the still life after Mondrian and left behind a glistening trail in its wake (Vanitas. After. Pitcher with Onions). The Léger replica fell victim to a stray dog’s attempt to mark its terrain (Pissed. After. Nature Morte). More intentionally, a portrait after Whistler has been kissed by a muse, Rasgaldo’s girlfriend leaving the marks of her lips on Dr. Isaac Burnet Davenport’s smooth forehead. A few of the paintings even went missing–stolen maybe, removed, or cleaned away much like Beuys’ famous fat corner, and might—who knows—reappear as originals someday, somewhere.

Rasgado himself then took to reworking the remaining paintings obscured under the veil of dust—working blindly through the thick blanket and unearthing traces, elements of the images, cleaning, excavating, exhuming the canvas, carving out an image and thereby employing the technique of a classical sculptor much rather than that of a painter. The forms laid bare by his manipulations differ greatly–sometimes they seem to be casual wipes across the surface, in other instances they are highly geometric and premeditated. Bellini’s Madonna has been rendered comically absurd, only eyes and mouth drawn into the dust to create minimal smiley faces, reminiscent as much of Cecilia Gimenez’ infamously botched attempt at restoring an Ecce Homo fresco in Zaragoza as it is of Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis of faciality being the eternal iteration of the “white wall / black hole system,” of surfaces (signifiance) defined by apertures (subjectification).

Several still lifes or natures mortes lurk under the coat of dust in Rasgado’s series. As a genre, they reflect the ambivalence of the nature of painting: While arresting nature and life into a static, immutable form and playing with symbols of decay and death as memento mori, they also transubstantiate a moribund object into an immortal artefact, dodging the bullet of temporality. Dust, as the ultimate reminder of transience, similarly can be reinterpreted as a perfect fertilizer in Rasgaldo’s Afterlife: as the white slate that facilitates the productive force of iteration, of anachronism and recollection.

Eva Wilson

pablo rasgado, A Bird. A Horn. A Leaf. After. Untitled (Deer in the Forest), 2014. Dust on Acrylic on canvas, 72,5 x 89 cm

Afterlife

VENUE:

Arratia, beer. Berlin

DATE:

2015

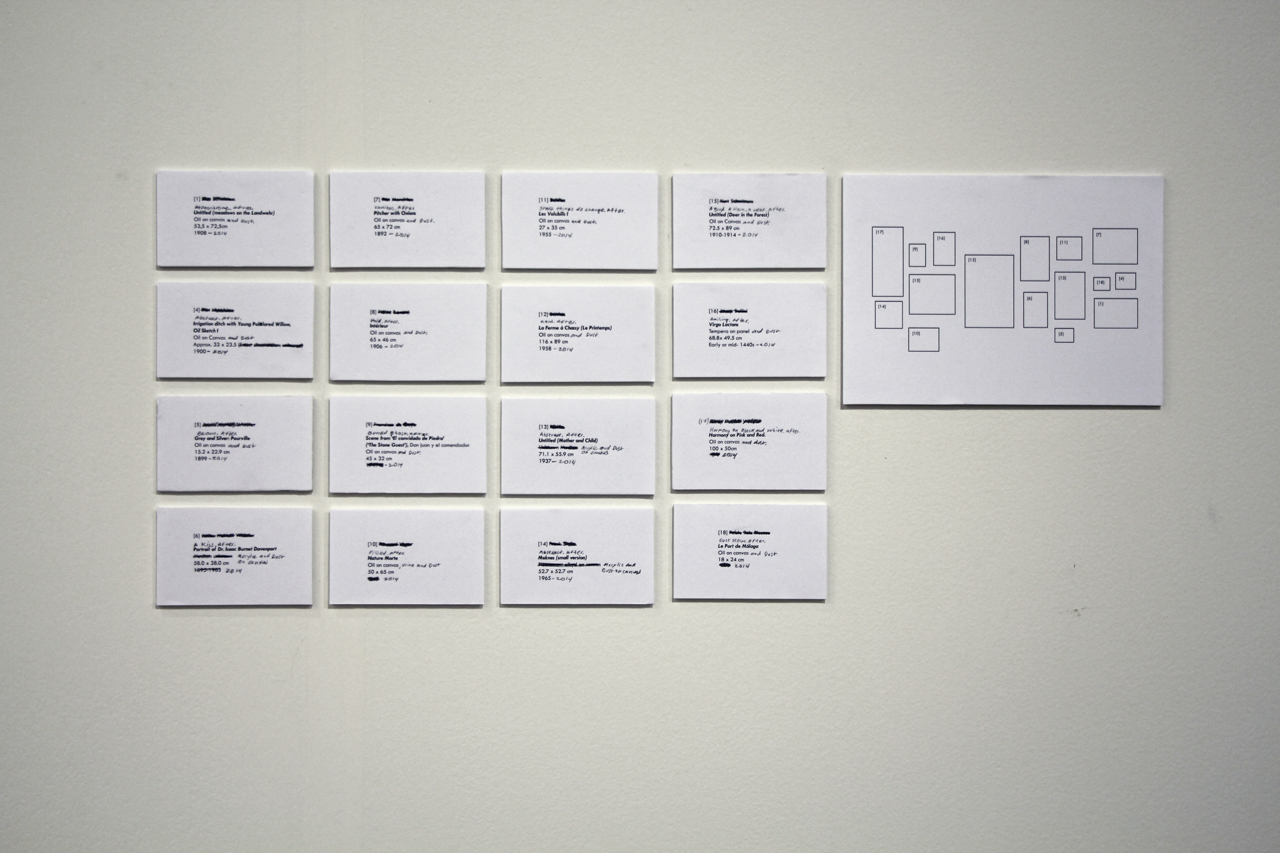

no. 01 - no. 2 - no. 3 - no. 4 - no. 5 - no. 6 - no. 7 - no. 8 - no. 9 - no. 10 - no. 11 - no. 12

Title

Afterlife

Date

2014-2015

Medium

Installation, dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

Variable measures

Afterlife

VENUE:

45ª ed. Art Basel, Statements. Basel, Switzerland

DATE:

2014

no. 01 - no. 2 - no. 3 - no. 4 - no. 5 - no. 6 - no. 7 - no. 8 - no. 9 - no. 10 - no. 11 - no. 12 - no. 13 - no. 14 - no. 15 - no. 16

Title

Afterlife

media

Installation, dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

Variable measures

Smiling. After. Virgo Lactans

no. 01

Title

Smiling. After. Virgo Lactans

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

68.8 x 49.5cm

Abstract. After. Untitled (Mother and Child)

no. 02

title

Abstract. After. Untitled (Mother and Child)

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

71.1 x 55.9cm

Rain. After. La Ferme à Chassy (Le Printemps)

no. 03

title

Rain. After. La Ferme à Chassy (Le Printemps)

Date:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

116 x 89cm

Monochrome. after. Untitled

no. 04

Title

Monochrome. after. Untitled

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

40x50 cm

Monochrome with eyes. After. Philip IV.

no. 05

Title

Monochrome with eyes. After. Philip IV.

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

180 x 120 x 15 cm

A kiss. After .Portrait of Dr. Isaac Burnet Davenport.

no. 06

title

A kiss. After .Portrait of Dr. Isaac Burnet Davenport.

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

58 x 38 cm

Monochrome. After. Untitled (meadows on the Landwehr)

no.07

title

Monochrome. After. Untitled (meadows on the Landwehr)

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

53,5 x 72,5cm

Abstract. After. Meknes (small version)

no.08

title

Abstract. After. Meknes (small version)

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

79 x 56 cm.

Static things. After. Les Volubilis I

no.09

title

Static things. After. Les Volubilis I

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

27x35cm

Brown. After. Grey and silver

no.10

title

Brown. After. Grey and silver

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

15.2 x 22.9 cm

Dust storm. After. Le Port de Málaga

no.11

title

Dust storm. After. Le Port de Málaga

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

18x24cm,

A Square. After. Maison Et Palissade

no.12

title

A Square. After. Maison Et Palissade

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

33 x 22cm

Vanitas. After. Pitcher with Onions

no.13

Title

Vanitas. After. Pitcher with Onions

DATE:

2014

Medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

65 x 72 cm

Abstract. After. Irrigation ditch with Young Pollared Willow, Oil Sketch I

no.14

title

Abstract. After. Irrigation ditch with Young Pollared Willow, Oil Sketch I

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust on oil on canvas

dimensions

33 x 23.5 cm

Pissed. After. Nature Morte

no.15

title

Pissed. After. Nature Morte

DATE:

2014

medium

Dust and urine on acrylic paint on canvas

dimensions

50 x 65 cm

projects