Ramificación

is a material and research project that investigates architectural typologies inherited across the “Atlantic triangle,” where the transatlantic slave trade left enduring imprints on methods of construction. The work explores how structures that appear local and isolated, in fact, reveal deep historical, cultural, and social connections linking communities in Africa, Brazil, and Mexico.

The project began with fieldwork on the Oaxacan coast, engaging with communities dedicated to building palm-thatch houses. These dwellings—constructed collectively through tequios (communal labor) and transmitted across generations—preserve architectural patterns that testify to cultural mestizaje and to the persistent memory of the African diaspora.

Ramification unfolds in two parts. The first is a visual and photographic archive of structural variations in communal houses across territories marked by forced migration. Known by different names—redondo negro or casa Huasteca in Mexico, quilombo in Brazil, arish in Africa—these dwellings operate as living archives, embodying both resistance and continuity.

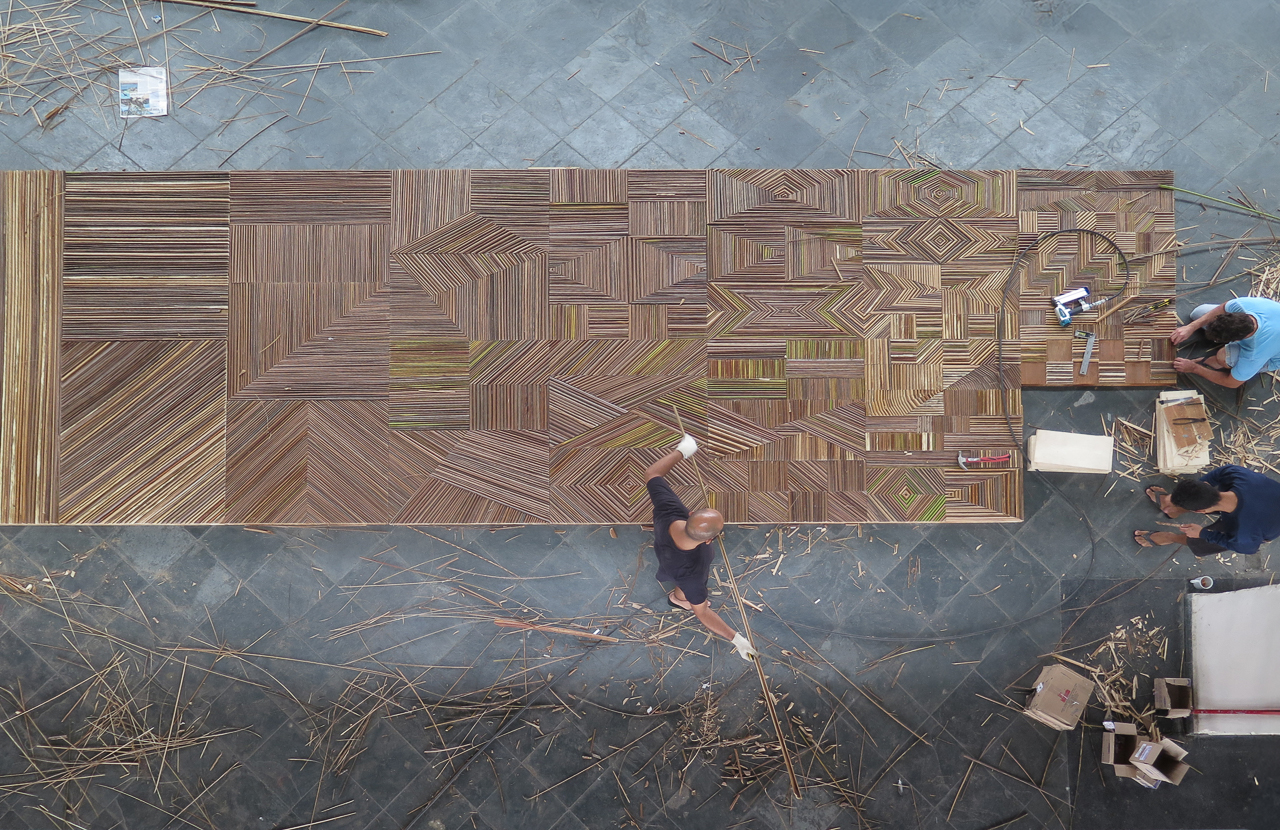

The second is a mural that translates inherited architectural patterns into an expanded pictorial language. Here, the surface functions as the “symbolic skin” of architecture: a space where forms, beyond their functional purpose, become carriers of social, historical, and spiritual meaning.

Following the logic of branching structures, Ramification connects architectural nuclei with their multiple variations, proposing a non-linear reading of history. At once archive, cartography, and mural, the work reveals a visual network that highlights cultural persistence and the invisible bonds that endure beyond borders and chronologies.

Materials

Architectural structures made with Palm leaves, and archival materials.

date

2015-2018

Exhibitions

⎖11th Mercosul Biennial

⎖Galeria Municipal De Arte Gerd Bornheim, Caxias do Sul

Collaborators

⎖Paula Borghi, Curator

⎖Alfons Hug, Curator

⎖CASA WABI, Facilitator

Texts

⎖ALFONS HUG

⎖PAULA BORGHI

⎖JOSE FRANCISCO ALVES

publications

⎖O TRIANGULO ATLÁNTICO - 11th Mercosul Biennial CATALOGUE

Texts

Published in:

⎖11th Bienal do Mercosul, Catalogue

Having focused primarily on Latin America in the past, the 11th

Bienal do Mercosul is now turning its attention to the Atlantic

region as a whole, or more precisely to that magical triangle

in which America, Africa and Europe have been fatefully intertwined

for the past 500 years.(…)

(…)The Brazilian quarter in Lagos, the old slave market in Rio and

indeed the quilombos form the axis that is also known as the

Black Atlantic: a complex network of centuries-old political,

economic and cultural components on both sides of the ocean

that extends from Rio de la Plata to New York and from Dakar to

Cape Town. Strictly speaking, Europe should also be included in

this, as it invented the slave trade in the first place and profited

from the transatlantic triangle.(…)

(…)Culturally speaking, the Black Atlantic of course became

incredibly productive thanks to its diaspora, giving rise to a huge

creolization process that spawned an intensive movement of

religions, languages, technologies and arts. Entirely different

views of nature, time and space changed and were reformed in

an extremely dynamic system. (…) The New World is the place where assimilations and superimpositions

were negotiated and in which the diaspora settled in a

terra incognita. It has become the embodiment of migration itself

– of travel, of a constant state of being on the move, and of an

uncertain return home.(…)

(…)Despite certain historical reference points, the biennale is all

about a contemporary configuration of cultural dynamism and

interdependence within the Atlantic triangle.

The actors in this transatlantic quest for clues are 70 artists

from all three continents, who explore the cultural tensions and

relationships within the triangle. They aim to discover which

innovative forces in the interplay of America, Africa and Europe

can be mobilized today.(…)

(…)The artists are interested in precisely those points of contact at

which indigenous, European and African cultures converge and

where, as a result, a new American amalgam is created. (…)However, contemporary art is also exploring the thorny issue of

the Atlantic triangle by addressing those conflicts and problems

that arise when different civilizations and social strata collide.

The biennale is focusing on the following five topics:

Atlantic crossings

African roots

Indigenous culture

Migration and diaspora

Individual and society

(…)A complex cartography of the Atlantic emerges in the works

of the artists from three continents. Historical approximations

collide harshly with modern-day realities, the Tropics with

temperate zones and documentary strategies with poetical

approaches. (…) Such an exchange becomes particularly productive

when for instance Afro-Brazilian artists conduct research in West

Africa, or when Africans work with Brazilian finds.(…)

(…)In all pressing political and social questions that may arise as

subjects time and time again, however, the biennale always

insists on the intrinsic meaning of aesthetic and poetical

processes that are abstracted from everyday life and its

loquacity and can therefore construct an alternative world.

The more dramatic the events, the more important the form

of the artwork becomes.

(…)

Published in:

⎖11th Bienal do Mercosul, Catalogue

It’s Calunga, yes! It’s Calunga! /Old black man told me, old black man told me / Where lady liberty lives / There are no shackles or masters*

The musical theme for Paraíso do Tuiuti, runner-up at the 2018 Rio de Janeiro carnival, was the history of Brazilian slavery from colonisation to the present. In celebration of 130 years since the Lei Áurea abolished slavery in Brazil, the samba school acted out that history, indicating the active racism in Brazilian society and difficulties faced by Brazilian workers. There is a latent need to address such issues and art is one of the most effective ways of doing so. This is demonstrated by the impact of the parade, which a few hours later went viral on the Internet, appearing as the most watched video on YouTube Brazil and the most commented topic on Twitter, for example.

What took place in February 2018 was not an arbitrary event: there is a clear urgency to address issues that are still concealed. Yet it is surprising when elements of performance and entertainment manage to communicate so powerfully events that are still kept silent. This force makes art, be it popular or contemporary, one of the principal ways of opening wounds and purging conflicts that are far from healed.

It is no accident that the 11th Mercosul Biennial opens with a performance of Baile Show by Rio Grande do Sul artist Romy Pocztaruk, which celebrates the persistence of street culture as an artistic force of freedom. In partnership with the percussion section from the Imperatriz Dona Leopoldina samba school and singers Felipe Cato and Valeria Houston, Romy Pocztaruk pays tribute to carnival, to the samba, to cultural diversity and to the Paraíso do Tuiuti samba school itself. Which is why to speak of the carnival here is also to speak of the Mercosul Biennial, to think of them both as manifestations that address related issues. And this impetus of addressing a history filled with trauma also contains the voices of many, be it through carnival or through an exhibition of contemporary art.

The Atlantic Triangle

The Atlantic Triangle outlines the union of Africa, the Americas and Europe in one single narrative, focusing on how Brazil has been shaped and reshaped in this complex story. It involves looking to the Atlantic and using art to see its stories unfold – those from the past and much from the present.

From a cultural viewpoint, the meeting of indigenous, European and African cultures formed the basis for shaping the culture of the Americas, many Americas. Cultural diversity is a crucial factor for understanding this triangular relationship, yet one should not be naïve about the violent historical processes that constructed it. Focusing on colonial exploration in both Africa and the Americas since the 16th century, the voyage of this great Calunga brought the winds and currents which opened seaways that changed the history of the world. The migratory currents that have narrated this Atlantic triangle for more than 500 years, be they voluntary or involuntary, are marked by great sadness and pain.

The forced migration of Africans enslaved by colonisers (regardless of whether they are Portuguese, English or Dutch, etc.) is one of the crucial factors for understanding the construction of the Americas, since “the more distant and isolated are the slaves from their native community, the more complex will be their change as a factor of production, the more profitable their activity”. In Brazil the enslavement of Africans was more efficient in economic terms than was the enslavement of native peoples, although the relationship of the Portuguese to the indigenous inhabitants was no less brutal.

It is not possible to be certain about the exact number of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas, but it has been estimated that around 10 million people were forcibly removed from their homelands, of which 6 million went to Brazil. The figure is uncertain not just because of lack of documentation, but also because of illegal trading. Comparing percentages with today, the African slave trade to the Americas displaced “the same” number of people as currently live in Portugal.

Accepting African slavery as one of the great holocausts in the history of mankind, there seems to be some conflict in noting how 18th-century European thinking managed to be both Enlightened and proslavery at the same time. Although the French Revolution of 1789 was based on ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, the same protagonists argued that the African slave would only be aware of freedom through work or that the process of work would have a re-humanizing effect. This dichotomy of judgement allowed philosophers to encourage the free will of some and the exploitation of others.

Furthermore, the Brazilian colony’s maritime trade was concentrated on the production of exchange values. It was more convenient to grow tobacco and manioc, or make cachaça cane spirit, for example, to exchange for adult Africans, than it was to invest in the production of food and their minimum living conditions. Enslavement was the great enterprise of mercantile capital; the barter of human beings and consumer goods carried the same weight on the scales.

Based on the trade of products in exchange for human beings, the maritime triangle between Europe, Africa and the Americas left its mark on the first three centuries of colonisation, when the African was considered as mere merchandise, an item marked by iron shackles and taxed by the crown. And to understand better how this black slave market operated, it is necessary to consider another force operating behind the caravels and their merchandise: a third power.

The church was so involved in human trafficking that in 1690 the governor of Angola included in legislation that the sale of slaves was committed only “to those who profess the law of Our Lord Jesus Christ to instruct them”. At the same time, not only were African religions forbidden on American soil, but captured Africans in their homeland were also subject to a series of rituals for forgetting their beliefs and origins. As the historian Luiz Felipe Alencastro explains, “Father Antônio Vieira interprets the slave trade as the ‘great miracle’ of Our Lady of the Rosary: removed from pagan Africa, black people could be saved by Christ in Catholic Brazil (…) the Dutch adopted a similar doctrine: the Calvinism prevailing in their American colonies would save the souls of the black people transported there.” Indeed, religion continues to act as an important bridge towards syncretic relationships to this day. Considering the direct reflections of these cultural and social reverberations today, the 11th Mercosul Biennial touches on diaspora movements from a contemporary and multicultural perspective. The force of creative practice in dialogue with history allows the exhibition to construct a line of thought that addresses issues related to an oceanic mixing of races in encounter with the arts. Looking attentively at migratory flows, it seeks to consider the relationship between individual and society and human behaviour and its organisation based on the crossing of that Atlantic.

The city and its individuals, the memory of that enslaved body (so that it should never again be found in such conditions) and the persistent strength of Amerindian peoples through centuries of genocide, are some of the highly important discussion points for understanding the 21st century. Fortunately, such issues are finding more space throughout the world, as demonstrated by the Paraíso da Tuiuti samba school. Neglected issues need to be addressed in a more sensitive manner, looking at other protagonists.

Remaining Quilombo communities

From the period of slavery to the present, quilombo communities established by fugitive slaves have established themselves as areas of egalitarian resistance. In addition to being key representatives of the history, strength and struggle of Afro-Brazilians, generations of quilombo residents operate in a family and community network, and it is common to see an interracial relationship between community inhabitants.

The Areal da Baronesa and Família Silva quilombos in Porto Alegre are examples of how these structures – now incorporated into the urban area of the city – persist against policies of erasing history, sanitisation and gentrification. In consideration of their cultural and social importance, São Paulo artist Jaime Lauriano and Brasília artist Camila Soato were invited be resident artists in dialogue with some of the quilombo organisations in Rio Grande do Sul, a state with 60 quilombo communities certified by the Fundação dos Palmares.

Jaime Lauriano worked during the month of March with quilombo communities in Porto Alegre and Pelotas. He began with the Familia Silva in Porto Alegre, situated in a neighbourhood with the highest land prices in the city, which has been persecuted, threatened and attacked by agents of property speculators for decades. Moving to the rural area of Pelotas, Lauriano worked in partnership with Patrick Chagas, an inhabitant of the Vó Elvira quilombo. The result of this experience was brought together in the exhibition “Terra é poder” [Land is power] at Casa 6 in Pelotas, with photographs of Vó Elvira inhabitants, their statements and craftwork.

Meanwhile, Camila Soato’s residency took place at Areal da Baronesa (Porto Alegre), which is recognised as having largely been constructed by the power of feminism handed down from generation to generation, through the work of women who, in addition to being housewives, were the family breadwinners, mostly by taking in laundry. Today the community is praised for its social activities, including the children’s percussion group Areal da Baronesa do Futuro, which demonstrates the importance of carnival in the construction of identity and social self esteem.

Soato ran a painting workshop in association with the Associação Comunitária e Cultural Quilombo do Areal [Areal Quilombo Community and Cultural Association] for a group of around 20 Areal inhabitants, all women, aged from 10 to 80. The result of this residency came together in a group exhibition at the association premises of all the paintings produced at the workshop.

The exhibitions organised by resident artists Jaime Lauriano and Camila Soato in collaboration with quilombo organisations are essential for understanding The Atlantic Triangle, acting as an invitation to discover a neglected reality.

And so, entering the waters of the Atlantic and the surprising power within them, the 11th Mercosul Biennial has constructed this intense and creative exhibition, and also recognises the triangular connection between carnival, contemporary art and quilombo communities.

*Extract from the samba lyrics for Paraíso do Tuiuti 2018 – Meu Deus, Meu

Deus, Está Extinta a Escravidão. [My God, My God, Slavery is Abolished]

pablo rasgado, Ramificacion, 2018. Architectural structures made with Palm leaves, 8x3m

on-Site Research

SITE:

El venado y agua zarca Oaxaca

DATE:

2015

projects