"_ _ _ _ (_ _ _ _ _ _)"

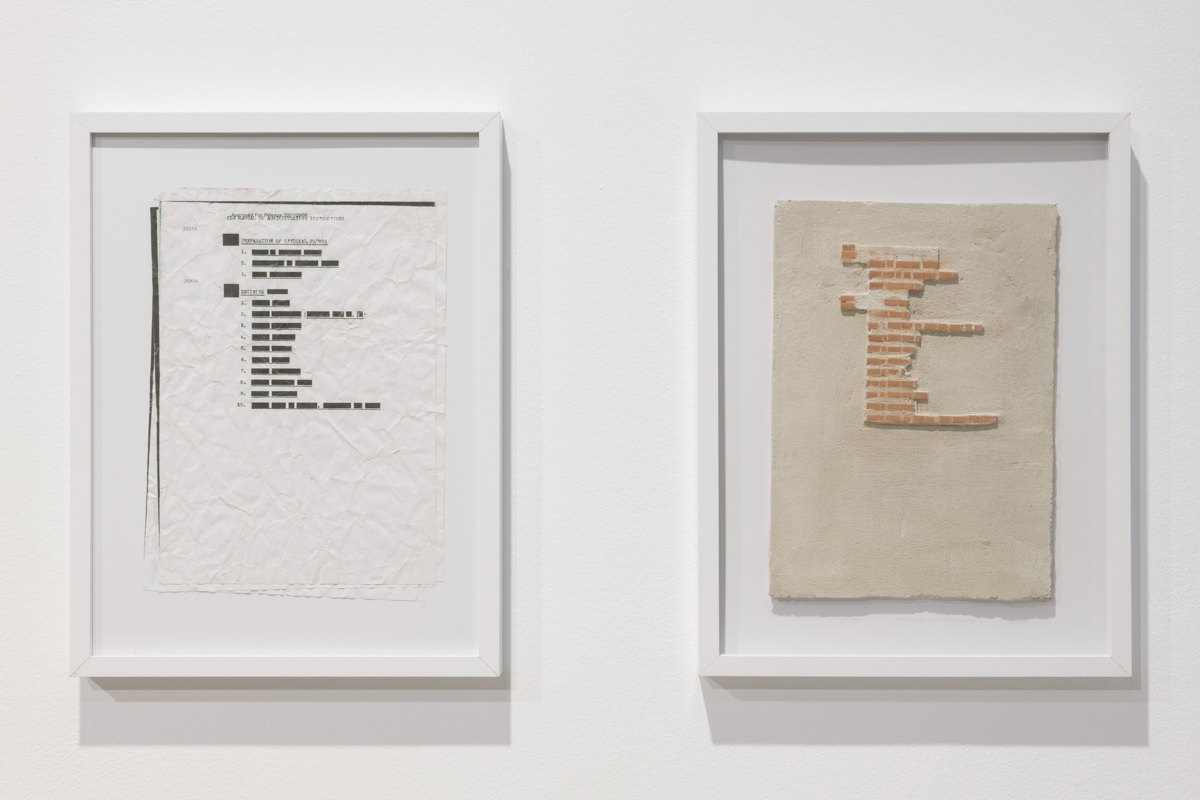

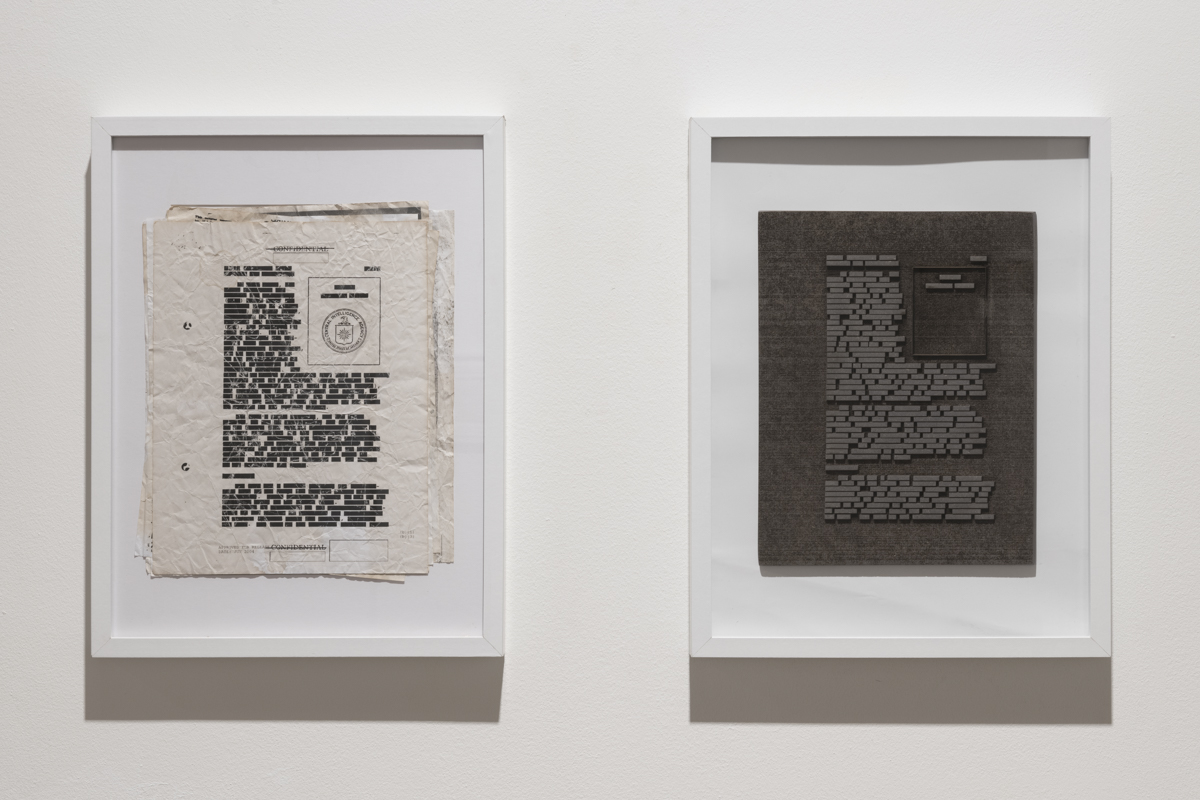

After obtaining a series of classified documents, the artist translated the redacted fragments into architectural blueprints for the construction of three-dimensional structures. The censored blocks of text were thus transformed into volumes that reveal seemingly recognizable spaces: fences, doors, and windows defined by the omissions, creating human-scale constructions placed in public spaces that highlight the fine line between the public and the private.

Materials

Each piece is composed by source document, an architectural model and the resulting sculpture.

date

2019

Exhibitions

⎖Blue Project Foundation

Collaborators

⎖Renato de la Poeta, curator

⎖pedro torres, facilitator

Texts

⎖Andrea Torreblanca

publications

⎖"_ _ _ _ (_ _ _ _ _ _)" ed. by Blue project foundation

⎖Revista Animal No.29 ed. by Enrique Giner

Texts

Blue Project Foundation

Published in:

⎖Exhibition text Blue Project Foundation

The Blueproject Foundation presents the exhibition “—– (— —– ——- — —-.)” by Pablo Rasgado.

The exhibition gathers a series of sculptures centered on secrecy and the concealment of information, each accompanied by the source material, and an architectural model. Each sculpture is based on pages from confidential documents that were first “sanitized” and then “leaked” into the public domain.

Sanitization is the process of removing confidential information from a document or other messages to make it suitable for broader distri- bution. This procedure aims to lower the classification level of a document, creating unclassified versions. In printed documents, this process is often executed by blocking out or removing parts of the original text using various methods. The result, in many cases, is an illegible and ruinous text.

The dissemination—or leaking—of sanitized documents has shifted the understanding of how public and private spheres interact, influenced by the form and content of the disclosed information. A selection of these documents, sourced from platforms such as WikiLeaks or FOIA, forms the basis of the sculptures presented in the exhibition. These sculptures are built from the structure and omissions within these documents, which are transformed into architectural blueprints for constructing each piece. The weight of censorship becomes tangible in three dimensions.

The relationship between these pieces and concrete poetry is no coincidence. In both cases, the architecture of the text, the blank spaces, omissions, and other graphic elements invite viewers to explore the visuality and the message contained within the text’s structure. Often, the blocks and redactions that pervade a text provide valuable clues—not about the content of the document itself, but about the state and control of vision and information.

Andrea Torreblanca

Published in:

⎖—– (— —– ——- — —-),” Catalogue.

If we could define the work of Pablo Rasgado (Jalisco, Mexico, 1984) as a process of bricolage in the manner of Claude Lévi-Strauss, we might not be far off. The anthropologist asserts that “the bricoleur is someone who is on the lookout for pre-transmitted messages, collecting them to turn them into new signs… someone who orders and reconstructs history using leftovers and fragments, fossil testimonies of an individual’s or society’s history.” Pablo Rasgado is, therefore, a meticulous bricoleur who does not settle for merely collecting and attaching fragments of past events but scrupulously reconfigures a new grammar from the remnants of stories that are not easily visible.

For this reason, his fascination with architecture is not linked to ornaments or functionality but rather to negative spaces, the hidden sediments behind walls, the residues accumulating in margins and corners. Among his investigative methods, we can glimpse traces of the modern liquid art described by Zygmunt Bauman, in which history is composed of waste, where the creation and destruction of things occur simultaneously—for instance, when wall surfaces are removed from the streets and relocated to art spaces, only to crumble into pieces.

Yet, unlike the Metzgerian destruction or Jacques Villeglé’s décollages described by the Polish sociologist, for Rasgado, the city represents only the very first phase of search and selection. His urban explorations are closer to those of a gatherer or glaneur in the style of Agnès Varda than to the situationist dérives from which unforeseen collages emerge.

Consequently, this initial phase as a cultural collector is complemented by an interest in dissecting structures, whether “social, linguistic, or spatial, that result in an organism,” as the artist himself states. While at first, his attention may focus on configuring new volumes and sculptural forms emerging from previous fragments, Rasgado ultimately uses architecture as a social mirror. He recognizes it as a scaffolding that shapes our tactics, routines, and behavioral policies, while also possessing a unique capacity to render things invisible and disguise them: architecture as a system of hierarchies, capable of empowering, sensitizing, concealing, and surveilling.

For his latest project, “—– (— —– ——- — —-),” Rasgado turns to architecture as a subterfuge to replicate other systems of power that, in turn, conceal archetypes of control. Drawing from a selection of classified documents, the artist formally transcribes fragments that have been redacted, erased, or blacked out in secret files into three-dimensional objects. The censored blocks of text are thus transformed into volumes that reveal seemingly recognizable spaces: fences, doors, and windows—supposed passageways nullified at the moment of their construction, left as disused vestiges.

In this case, architecture subtly proposes itself as an act of resistance, a social structure where public and private domains enter into an unreadable and sly tension. With these new architectural riddles, Rasgado concludes his role as a bricoleur: one who transforms the remnants of a contemporary society into new signs.

pablo rasgado, _ _ _ _ (_ _ _ _), 2019. brick, cement, source document and maquete. 140 x 120 x 15 cm. Exhibition view, blue project foundation, 2019.

“_ _ _ _ (_ _ _ _ _ _)”

VENUE:

BLUE PROJECT FOUNDATION

CURATED BY:

⎖Renato de la Poeta

DATE:

2019

no. 01

Title

_ _ _ _ (_ _ _ _ _ )

DATE:

2019

Medium

brick, cement, source document and maquete

dimensions

Variable measures

no. 02

Title

_ _ _

_ _ _ _ _

_ _ _

_ _ _

DATE:

2019

Medium

wood, source document and maquete

dimensions

Variable measures

no. 03

Title

_ _ _ _

_ _ _ _

_ _ _ _

DATE:

2019

Medium

wood, window, source document and maquete

dimensions

Variable measures

no. 04

Title

_ -_ -_- _

_ -_- _- _

_ _ _ _

DATE:

2019

Medium

wood, window, source document and maquete

dimensions

Variable measures

no. 05

Title

_ _ _

_ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _

DATE:

2019

Medium

Brick, cement, source document and maquete

dimensions

Variable measures

projects